Winter Solstice Running Motivation

Today, while running some of the trails over Boulder in the cold temps and falling snow, I was reminded of one of my favorite short films – The Runner in Winter. It’s a great profile of ultra runner Anton Krupicka, and it also showcases many of my favorite area trails, particularly the trails up and around Green Mountain. The film provides some great motivation to get out and enjoy the snowy trails, even on the coldest of days. Enjoy!

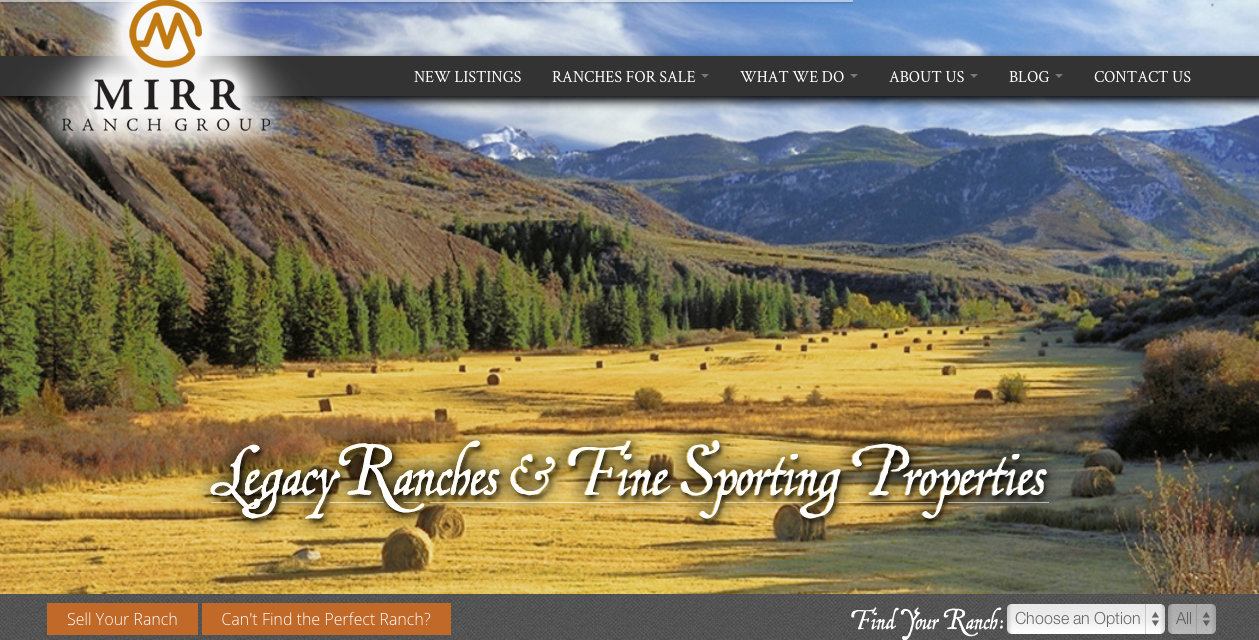

Ranch Marketing on the Web

A well-designed, photo-centric website is a mandatory tool for marketing high value, Rocky Mountain ranches. Check out this week’s post on the Mirr Ranch Group blog to learn more:

Boulder in the News

Excellent article in this month’s Inc. Magazine about Boulder, Colorado and its emergence as a hub of entrepreneurial activity.

Why Do Entrepreneurs Love Boulder?

“Outdoor sports lovers and entrepreneurs share a common DNA: ‘Thrill seekers are drawn to this place,’ he says. ‘Once you get out here, you want the ultimate thrill in business, too, and that’s start-ups.’”

Mapping Ranches

Despite unprecedented advances in mapping technology, I still routinely receive sloppy, crooked, hand drawn maps from brokers who are attempting to market multi-million dollar ranches. My new post on the Mirr Ranch Group blog describes some of the non-crayon mapping technologies that we use to effectively communicate the complexities of large Rocky Mountain ranches:

Ranch Marketing Tools, Part 1: Mapping

Our Gear and the Stories That Go With It

I’m a huge fan of Patagonia – the gear, the company’s mission, the company’s founder, and the lifestyle that the brand promotes. If you don’t know much about the company, I suggest reading this article about Patagonia’s founder Yvon Chouinard, reading this book, or watching this movie. Chouinard has a unique perspective on business – I actually read his book during graduate school and it had far more of a lasting effect on me than any of the finance books I studied.

For the last few years, Patagonia has been using the shopping-fighting-stampeding idiotfest known as “Black Friday” as an opportunity to promote the idea that you don’t need to buy a bunch of junk; consumers should value quality over quantity. This year, they’ve produced a film that highlights not only the high quality of their gear, but the idea that gear that has been truly used – torn, dinged, beat up, or destroyed after years of adventure and travels – is actually more valuable than anything you could buy new at a store.

And I couldn’t agree more. I bought a capiline base layer in 1999 that’s been with me through a semester of NOLS, a climbing trip to the Andes, two slogs up Denali, not to mention weekly runs, camping trips, and just working in the yard. I have a pair of Patagonia surf trunks that I literally wore 6 days a week for a year straight when I lived in Central America. I would know it was time to wash them when my wife complained that they smelled like vinegar and/or sausage. In those trunks, I surfed by first double overhead wave, was shaken down for cash by Nicaraguan police, and attended multiple “rodeos” that consisted of dozen of drunks taunting an angry bull and eventually being stomped or gored by said bull.

I could go on and on about the stories attached to my gear – particularly Patagonia gear because it lasts so dang long. Even when my trunks or capiline become too destroyed to wear, I’ll never throw them away – there are simply too many stories of fun, adventure, and craziness associated with each piece. It’s like Steve House says toward the end of the video: “To get rid of it, it would be like throwing away a journal.”

Wildlife on Ranches

Check out today’s posting on the Mirr Ranch Group blog:

Wildlife on Ranches – A Useful Research Tool

The article gives a quick overview of the Colorado Hunting Atlas, an excellent tool for researching the presence of big game anywhere in the state of Colorado. I’ve found this tool to be useful on many occasions, but particularly for double checking people’s claims of “trophy elk” on the properties they are trying to sell. While photos and stories of large elk are nice, I always like to have third party validation!

Indian Peaks Adventure

28 miles, 7,000 feet of vertical gain/loss, up & over the Continental Divide twice – Check out my new post on the Mountain Khakis blog about a late summer adventure in the Indian Peaks Wilderness:

Pawnee – Buchanan Pass Loop Trail

Beetles & Fire

Many people assume that beetle infested forests are more susceptible to destructive forest fires than healthy, green forests. Interestingly enough, scientific data is proving this assumption to be wrong.

Check out my new post over on the Mirr Ranch Group blog to learn more:

Bark Beetles & Forest Fires – A Common Misconception

CNN’s “Inside Man” – Drought, Ranchers & Ranches

I generally don’t like watching television, but there are a few shows that I’ll tape (or DVR or Tivo or whatever the kids are calling it these days) to watch when convenient, without ads. One new show that I’m really enjoying is CNN’s “Inside Man” which is directed by, and stars, Oscar-nominated documentary filmmaker Morgan Spurlock.

One of Spurlock’s previous films was “Supersize Me,” where he ate nothing but McDonalds for a month and suffered some serious and disgusting health problems in the process. I’ll never forget the scene where he’s trying to down his second or third Big Mac of the day and ends up puking all over the Mickey D’s parking lot. But I digress….

In his new hour-long show (40 minutes without ads), he examines many controversial issues including immigration, elder care, and bankruptcy. All of the shows are eye opening and educational, but also entertaining. In one of his more recent shows, he investigates the drought that has been plaguing the America West for the better part of the last decade. In this episode, Spurlock follows a Nebraska ranching family whose cattle operation has practically imploded because of the lack of rain – which translates into lack of grass – which translates into not being able to raise cattle.

Over the course of the show, we see the family having to sell off cattle because they simply don’t have enough grass on their 11,000-acre ranch to feed their herd. Buying supplemental hay or feed is not an option, because the price of both has skyrocketed to the point that it doesn’t add up financially. We see where a prairie fire scorched a portion of their ranch, effectively reducing their cattle carrying capacity by half. We watch them trying to protect the small amount of hay they did mange to grow from thieves, who have begun systematically stealing it because of its high value and scarcity. We even see them visit their local banker’s office, weighing the pros and cons of completely shutting down their ranching activities and liquidating their assets.

As unsettling as it is to watch this family’s struggles, it even more disconcerting to think that this same drama is being played out in every ranching community, all over the American West and Mid-West. I appreciate Spurlock bringing this issue to the forefront, because it seems that most “news” outlets (CNN included) are more focused on Kim Kardashian or American Idol than real issues like this ongoing debilitating drought. No matter where you live, the drought is real issue that directly affects our economy, our national security, and our national identity.

Set your DVR or VCR to record the show. You’ll be smarter because of it.

Colorado Ag Network – Summer Happy Hour

If you’re going to be in Denver next Thursday, August 15th, be sure to join us for the Colorado Ag Network’s Summer Happy Hour. We’ll be meeting from 4:30-6:30 at Del Frisco’s in Greenwood Village, and our guest speaker will be Mr. John Stulp, Special Policy Advisor to the Governor for Water.

You can find directions and additional information here: Colorado Ag Network – Upcoming Events

For those of you unfamiliar with the Colorado Ag Network, it is a relatively new networking group that was created with the purpose of bringing together leaders from Colorado’s agriculture and conservation sectors, so that they can meet, get to know each other, and discuss ideas in a casual, relaxed setting.

Historically, farmers and ranchers have found themselves at odds with conservationists (and vice versa) when it comes to political ideology and certain land use issues throughout the Rocky Mountain West. However, when you take a step back, it is fairly obvious that many reasonable conservationists and level-headed ranchers share similar goals – More times than not, they both want to preserve and enhance Colorado’s agricultural communities, natural resources, wildlife habitats, and scenic open spaces. Their means to those ends may be different, but there is no denying that the two groups share many goals.

The Colorado Ag Network is a place where folks from both sides can come together, have a drink, and discuss their goals, similarities and differences in a friendly, welcoming atmosphere. The first two events were resounding successes, and we anticipate the positive forward momentum to continue.

For more information on C.A.N. – the mission, core values, and leadership – please visit the Colorado Ag Network website.

Hope to see you there!

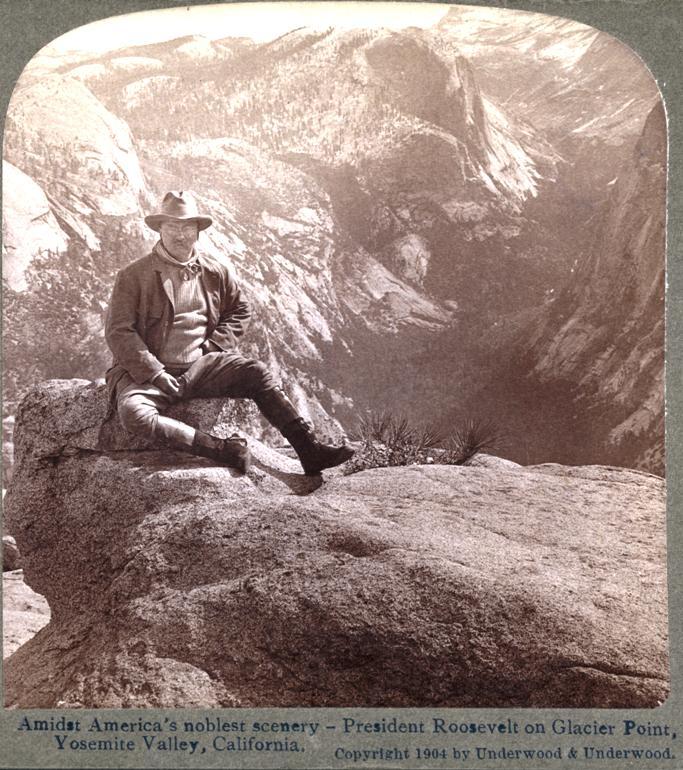

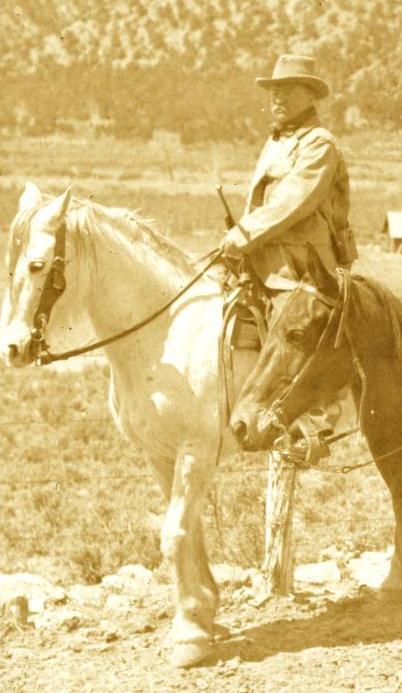

T.R. on Hard Work and the West

An great quote from Theodore Roosevelt, written to his lifelong friend William Sewell during T.R.’s Badlands ranching days. Although written in a completely different time and context, I think the quote still holds true today regarding life and work in the Rocky Mountains:

“Now a little plain talk, though I think it unnecessary, for I know you too well. If you are afraid of hard work and privation, don’t come out west. If you expect to make a fortune in a year or two, don’t come west. If you will give up under temporary discouragements, don’t come out west. If, on the other hand, you are willing to work hard, especially the first year; if you realize that for a couple of years you cannot expect to make much more than you are now making; if you also know at the end of that time you will be in the receipt of about a thousand dollars for the third year, with an unlimited field ahead of you and a future as bright as you yourself choose to make it, then come.”

– Theodore Roosevelt letter to Sewall, 6 July 1884

(Thanks to The Almanac of Theodore Roosevelt for the quote)

Ted Turner + Bison + American West

Another interesting Ted Turner article, this one from the good folks at The Land Report. I’ve worked with a number of bison ranchers over the years, and it’s undeniable that Turner and his restaurants have played a pivotal role in the reintroduction of bison throughout the American West.

“Ted didn’t want to be in the cattle business. He didn’t want to be in the hay business. He didn’t want to be in the oil and gas business. He wanted to be in the bison business because it would rekindle America’s West the way it was.”

Sixteen Million Bison Burgers Later …

(If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you know that I’m somewhat obsessed with the bison and have read and reviewed several books about North America’s Most Interesting Animal. I definitely recommend learning more about this unbelievably powerful and historically significant animal!)

Ted Turner – Western Art, Land Stewardship, and Business

I just came across this interesting article in Western Art and Architecture magazine about Ted Turner, his love of Western Art, and how that passion for art has guided some of his land acquisitions and stewardship efforts. Even though I’ve read every book that I know of on Ted Turner, this article shed some new light on the roots of his love for Western landscapes.

Article: Ethos by Todd Wilkinson

Incidentally, the article was written by Todd Wilkinson, the author of Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet. I just finished Last Stand and will be posting a review of it in the next week or so.

Ranches and Private Equity

Be sure to check out this interesting article in today’s Wall Street Journal about several private equity funds that are purchasing large western ranches, improving their fisheries and wildlife habitat, and reselling them at a profit:

I’ve had the opportunity to work with several of these groups over the past few years, and I personally admire the way they are able to bring together governmental, non-profit, and traditional business groups to simultaneously improve the natural landscape AND turn a profit for investors.

Camping in Rocky Mountain National Park

My wife and I spent the weekend camping and hiking in Rocky Mountain National Park, enjoying some of the most scenic and spectacular terrain in Colorado. While RMNP (and most other National Parks) can get rather crowded during the summer months, it amazing how few people venture more than 2-3 miles into the backcountry.

We hiked up to Sky Pond, a small glacial lake just east of the continental divide at an elevation of around 11,000 feet. After passing Alberta Falls, most of the other hikers quickly thinned out, and, by the time we reached Sky Pond, we were the only people around.

If you find yourself in Northern Colorado, I highly recommend spending at least a day in RMNP. There’s unbelievable scenery, abundant wildlife, and fun outdoor activities for all ages and ability levels.

(Also, my new listing Three Creek Ranch is actually located just 30 minutes from the Park’s western entrance in Grand Lake – just another feature that makes it such a unique property!)

A few additional photos from the day:

Grazing elk in Moraine Meadows

Sunset in the Park

Rising moon over the Continental Divide.

Loch Vale

Waterfall just below Sky Pond

Taking a very cold, very quick swim in Sky Pond!

Afternoon in Moraine Meadows

Summer in Red Feather Lakes

Over the weekend, I had showings on both of my ranch listings near Red Feather Lakes, Colorado – Phantom Lake Ranch and the Jensen Ranch. Given the huge amount of April snowfall, both ranches are just now reaching their full summer greenness. On both properties, the water was flowing and flowers were blooming, making it a perfect day to spend outdoors, with great clients, in the Colorado mountains. Enjoy these photos from the day:

Top 3 Conservation Updates

Head over to the Mirr Ranch Group Blog to read my most recent blog post:

This Spring’s Top 3 Colorado Land Conservation Updates

And speaking of conservation, the photo above is from my most recent trip to the Jensen Ranch, a unique 174-acre Forest Service inholding that has been conserved by Northern Colorado’s Legacy Land Trust.

Quandary Peak Sunset

After a full day touring ranches, I decided to make a quick trip up 14,265-foot Quandary Peak before starting the two hour drive back to Boulder. I didn’t leave the trailhead until 6:30 PM, so I had to move fast to catch the sunset. My timing could not have been better.

MK Blog Post – Colorado Fly Fishing

Head over to the Mountain Khakis blog for a new post on fly fishing in Colorado’s South Park basin:

Fly Fishing Adventures in South Park (not the cartoon)

I’ve been a fan of Mountain Khakis apparel for years – I’ve found their clothes to fit perfectly with my professional and personal outdoor lifestyle. Given that a normal work day for me can include everything from climbing over barbwire fences to hiking ridges at 11,000 feet to face-to-face client meetings, I appreciate MK’s durability, versatility, and professional appearance.

I’m excited to be teaming up with them as an MK Ambassador. I’ll be contributing several blog posts and photos per year, so keep an eye on their site!

Spring Calf Branding in Wyoming

This past Memorial Day weekend, my wife and I headed up to Wheatland, Wyoming for a client’s annual spring calf branding. We worked our way through around 250 calves – roping them, wrestling them to the ground, then vaccinating, branding, and (if necessary) castrating them.

It was tough, dirty work, but there’s something very special and historically noteworthy about participating in spring branding in the Rocky Mountain West. I love to think that (minus the vaccines and the propane flame for the branding iron), the exact same scene was playing out over 150 years ago: neighboring landowners coming together to rope and brand, then enjoy a big meal together after the hard work is complete.

Enjoy these photos from a great day:

View from the top of Colorado

After a few days on the road with minimal exercise, I decided to give my legs a test on Mt. Elbert, the highest mountain in Colorado (14,433 ft). I didn’t leave the trailhead until around 3:30PM, but I made great progress up and down the northeast ridge, finishing before dark and making it back to Boulder in time for a somewhat reasonable bedtime.

Despite the fact that I had to posthole through thigh deep snow (in shorts!), I was glad to see that there’s still a good amount of snow up top. Given last summer’s terrible drought conditions, we need all the moisture and snowpack we can get.

Spring in Winter Park

Spring skiing at Winter Park… No crowds! Grand County, Colorado.